The Scooby-Doo ladder magnate isn’t just a cartoon punch-line, he’s a warning label. For forty years, Silicon Valley has been trained to worship businesses that compound indefinitely: SaaS dashboards that bill monthly, network effects that snowball, and margins that expand with every extra user.

Deep-tech plays in larger markets than SaaS but by a very different rulebook. Many businesses look less like revenue compounders than process compounder [1] and the revenue you do have looks like a discovery of gold. Finding gold is rare and it’s not necessarily a given you can strike it twice.

My Gold Mine Business

I have first-hand experience with this, because I ran a gold mine: Rent the Backyard. which built ADUs (backyard homes) across the San Francisco Bay Area. The mine was deep (>100,000 suitable backyards in San Jose alone) but obviously a mine. We weren’t particularly worried about exhausting the market though — ADUs were our initial way to build affordable housing.

At just over 400 square feet (40 square meters), we thought of our ADUs as “minimum viable housing” we could quickly get cost effectively reps building. Built with a flat roof from cross laminated timber, we envisioned combining modules into larger single units or stacking them into multifamily units.

Spoiler: We were killed by small scale production and interest rates, not by running out of gold [2].

Anatomy of a Gold Mine

Once you start looking for them, gold mines are remarkably common. Physical installations, financial / technology arbitrage, and products well loved on “r/BIFL” (Buy it for Life) all share the same defining characteristic:

- One-and-done customers: You sell to a customer once. There’s no LTV (Lifetime value) calculation, no upsell path, no recurring revenue from the core product. The entire economic value of the relationship is captured in a single transaction [3].

This leads to

- Depleting TAM: every sale by you (or a competitor!) reduces the potential customers for your product.

- Depleting customer quality: just like a real miner you go after the more accessible and profitable seams of gold first. Subsequent customers are further from your ICP (ideal customer profile), your sales process gets more difficult, and margins decrease as you grow [4].

- Gold rush: running the business isn’t about growing the pie, it’s about gorging yourself until it’s gone. If you don’t already have competitors they’ll be here soon.

Struck Gold or Printing Money?

Most real-world businesses sit somewhere between a pick-once gold mine and an always-on SaaS subscription. Two variables matter more than anything else:

| Axis | Question | Gold Mine Extreme | SaaS Extreme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repurchase cadence | How often does the same customer need you again? | Once a ~decade. (Casper) | Every second you’re awake. (Slack) |

| Revenue elasticity | Can you keep charging for more value over time? | One fixed ticket. (LASIK vision correction surgery) | Expanding seat count, usage-based billing. |

Trying to be SaaSy

The easiest way for most software companies to grow is by increasing revenue from existing customers. Gold mine companies don’t do this!

At Rent the Backyard, we were often encouraged to sell homeowners ancillary or reoccurring services like property management or insurance. Unfortunately, commissions from $50 / month insurance or even $200 / month property management couldn’t move the economics on a $200,000 ADU purchase. Solar panels or battery systems might have been a little better but there wasn’t a conceivable way to double or triple the margins on an installed project [5].

Casper spent millions trying to improve the economics of its $1,000 mattress business by selling $50 pillows. The business was bought by private equity for 1/3 its IPO price after two years on the NYSE.

At both companies, it was much better to invest in the core product than ancillary revenue but all companies exist somewhere on the spectrum between mining for gold and selling SaaS.

Mapping the Gold-Mine-to-SaaS Spectrum

| Business | Why It Lives There | Attempt to be SaaSy |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Mine: LASIK vision correction surgery | You only need to correct your vision once (and it’s literally unhealthy to do twice) | “Lifetime guarantee” conditional on annual eye exam |

| Casper mattresses | 10+ year replacement cycle, no built-in add-ons. | Release pillows, dog beds, CBD sleep drops — anything to manufacture frequency. |

| Tesla & Peloton | Durable hardware, but software subscriptions or purchases can add meaningful revenue | Convert one-off buyers into subscribers. Shorten upgrade cycles. |

| Airbnb Guests | Guests often book once for a wedding or vacation. | Cater listings toward remote workers. Offer loyalty perks and business-travel tools |

| Apple iPhone + App Store | iPhone itself is a 3- to 4-year good, but the services layer renews daily. | Subscriptions and ongoing spend (iCloud, TV+, Apple Pay Later) |

| SaaS: Slack | Metered or seat-based billing, near-zero marginal cost. | Increase usage and switching costs |

Solar Leasing’s Jevon’s Paradox: Growing a Gold Mines to Death

As residential solar panels first became available in the early 2000s, companies like Sunrun and Solar City (now owned by Tesla) were textbook examples of a gold mine business. Massive sales teams went door-to-door signing up homeowners for “solar lease” loans to put solar panels on their roof to save on their utility bills. It was an easy sell: your monthly payment on the solar panel was less than what you’d save on electricity.

At first the market was a true gold mine. There were a finite number of correctly angled, suitably sunny roofs owned by people with good enough credit. Once a house got a solar installation, it was off the market [6].

But then solar kept getting cheaper.

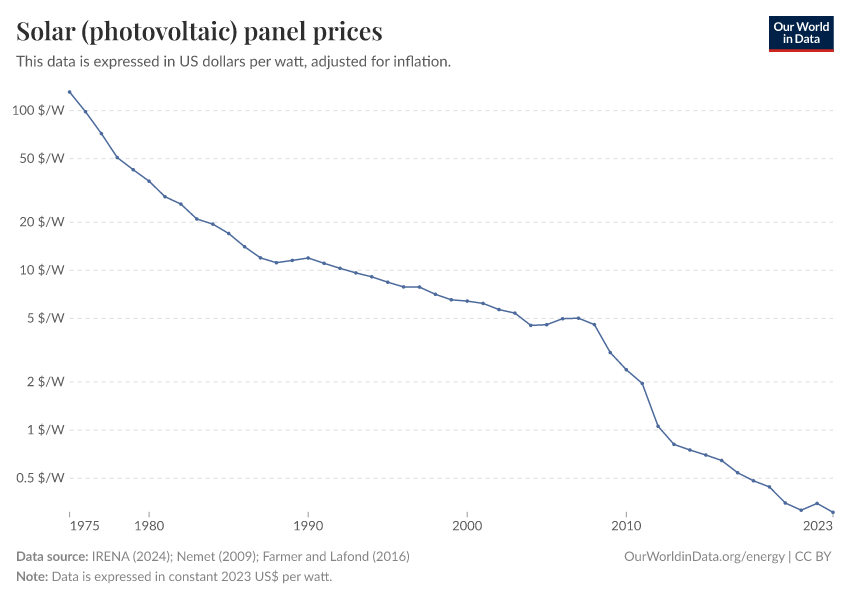

The Y-axis (cost per watt) is a log scale 😳

The number of homes solar leasing companies could service rapidly expanded [7] giving the companies more TAM to mine but the costs kept dropping. When Sunrun was founded in 2007, a 7 kW system to power a 2,000 square foot house cost ~$60,000. In 2025, that same system would be only ~$14,000 [8].

Unfortunately for Sunrun, low prices also meant consumers didn’t really need to finance solar panel as much either. Sunrun’s stock is about the same price as when it IPO’d in 2015.

Gold Mine Mistakes

If you realize you’re running a gold mine, you have to fight the instincts you’ve learned from reading about or running typical venture-backed startups [9].

Mistake #1: Confusing Yourself with a “Growth” Startup

The single biggest error a gold mine company can make is subsidizing customer acquisition. As a gold mine company, you will make ~all of your money at the time of acquisition or on some short half life thereafter.

The easiest way to recognize a startup that doesn’t know they’re a gold mine business is to see them losing money on CAC. In a normal startup, you might justify that with high LTV or !network effects! But here, the transaction is the beginning and the end. There is no “later” to make it up on volume. You are just lighting money on fire.

Mistake #2: Staying in “Growth Mode” for Too Long

The lifecycle of many gold mine company can be brutally compressed: Growth -> Plateau -> Decline. You have to be ruthlessly honest about which phase you’re in. If you’re in decline, you can look for clever ways to reinvest in growth or new business lines, but you might never find anything as good as the original business!

It’s okay if you can’t find anything worth investing in but your job becomes gracefully managing decline and creating the best outcome for your stakeholders, employees, investors, and yourself [10].

Mistake #3: Returning Capital the Wrong Way

Without a growth story, declining companies have a share price that’s hard to predict but presumably decreasing. While conventional wisdom is now that buying back stock is mechanically ~identical and more tax efficient than issuing dividends, this only applies to companies with a flat or rising market capitalization!

The worst mismanagement of a declining company? IBM:

The company spent ~$200 billion buying back their stock between 1995 and 2019. As recent as November 2023, IBM’s market cap was only ~$100 billion.

The stock has risen with the AI wave to ~$275 billion as of July 2025 and the company has finally switched to paying a ~$6 billion dividend instead of buying back more stock.

Sunset of Pivot

IBM’s buy-back folly shows what happens when a finite-growth company pretends there’s more gold in the mine. The cash would have served shareholders far better as dividends (or even better if they would have built their Watson Jeopardy playing AI into ChatGPT).

If you think you’re running Rung Ladderton’s ladder company, here’s the playbook:

| Phase | What You Do | What You Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Exploit | Price for margin, not share; recover CAC in months, not years. | Subsidize acquisition “for growth.” |

| 2. Harvest | Pour operating cash into dividends or a clearly superior adjacent bet. | Chase low-ROI “synergies” just to keep the music playing. |

| 3. Sunset (or Pivot) | Shrink with dignity: cut fixed costs, keep service quality, communicate early. | Hide decline with creative accounting or heroic share buy-backs. |

How to Win as a Gold Mine

When the gang finally unmasks Rung Ladderton, he snarls, “I could’ve made it work, if it weren’t for you meddling kids!” The truth is simpler: no amount of villainy, or venture accounting, turns a non-recurring product into a compounding engine.

Gold mine companies aren’t “bad” businesses. They can be incredibly lucrative and strategically valuable. But they are fundamentally different to run than a quintessential software business. The key is self-awareness. Know what kind of company you are. Mine your gold, be smart about how the business can grow, and know when to distribute the spoils.

Notes

[1] Companies that can internally compound their engineering culture, ambition or underlying processes (eg Musk’s belief “the factory is the product”) are probably the businesses most likely to win in the long run.

- OpenAI’s uses the same staff to build successive new products that each monotonically decrease in cost.

- SpaceX has the lowest cost launch today but is focused on going to Mars and doesn’t patent its core rocket technology.

- Facebook benefits from an incredible network effect but it’s “move fast and break things” engineering culture has helped it copy or buy anything new in social media for the last 20 years.

[2] Reading this piece again a few years removed I also think we didn’t charge enough. We wanted to be the Toyota of the market (cheap homes for everyone, not custom homes for the upper middle class), but we pursued that a bit too dogmatically. Until the very end we missed opportunities to upsell customers who would have happily paid for fancier fixtures, landscaping, and small custom additions. Pricing low, slow production, and construction inflation cut our backlog of projects (and the CAC embedded in them) from profitable to break even and eventually unprofitable.

[3] All of the economics might be captured in a single transaction but it might take a while for all the revenue to arrive (maybe you are paid monthly for 20 years like a solar least) and there is some stochastic risk on the backend.

[4] There’s an idyllic conception of the California Gold Rush as a time when prospectors with only a pan easily pulled gold from pristine rivers next to Sutter’s Mill. This was the case for the first few months, but those surface deposits were quickly exhausted. Most of the gold harvested in California was from large operations that exploded rock underground, smashed to bits in giant machines and then run through a sludge of mercury to catch the gold flakes.

[5] The business did have an upsell opportunity at the customer level though: many of our customers were property investors with multiple properties that could have an ADU installed. This was meaningful for the ADU industry as it descended into a CAC war.

[6] There was actually a second gold mine here: Federal Investment Tax Credits (ITC) for solar installations that made up ~half of early economics. From Sunrun’s S1: ”Federal Investment Tax Credit (“ITC”). Tax incentives have accelerated growth in U.S. solar energy system installations. Currently, business owners of solar energy systems can claim a tax credit worth 30% of the system’s eligible tax basis (or the fair market value). While the tax credit for third-party-owned systems is set to step down to 10% on January 1, 2017, we expect the impact of any reduction to be mitigated by declining costs, rising electric rates and additional sources of low-cost financing.”

[7] A home in Maine (worst state for solar) needs a solar system ~22% larger than in CA to generate the same amount of power

[8] Prices before tax incentives. Post incentive prices would be ~$40,000 in 2007 and ~$11,000 in 2025.

2007 panel cost: $5 / watt x 7,000 kW = $35,000

2024 panel cost: $0.16 / watt x 7,000 kW = $1,120 — a 96.8% decrease over 17 years

Permits, installation, etc cost $5,000 - $8,000. Many customers also now add batteries which keeps the price a bit higher and make the leasing business model a bit better.

[9] Choose who advises your company very carefully! Silicon Valley is so SaaS pilled that >95% of randomly sampled investors, advisors, and employees won’t understand this dynamic and will encourage you to run the business sub-optimally.

[10] Maybe you will find something to use your gold mine as a launchpad to reach. But be intellectually honest: if the new business is so good why aren’t you just doing that right now? Be very skeptical if you can’t find a good reason. All companies have a lifespan and some are shorter than others. Gold mines produce incredible outcomes — just don’t spend all the proceeds continuing to mine when there’s nothing left!

Comments

You are seeing this because your Disqus shortname is not properly set. To configure Disqus, you should edit your

_config.ymlto include either adisqus.shortnamevariable.If you do not wish to use Disqus, override the

comments.htmlpartial for this theme.