Dancing with Missiles

16 Jun 2025I wrote this essay back in school after spending months interviewing veterans and poring over declassified mission logs from the squadron my grandfather flew 100+ missions with during the Vietnam War.

The Wild Weasels were the “first in, last out” volunteers who intentionally drew fire from surface-to-air missiles to protect the strike packages behind them. I’m still struck by how much their story says about courage, politics, and the uneasy art of fighting a limited war under the shadow of super-power escalation.

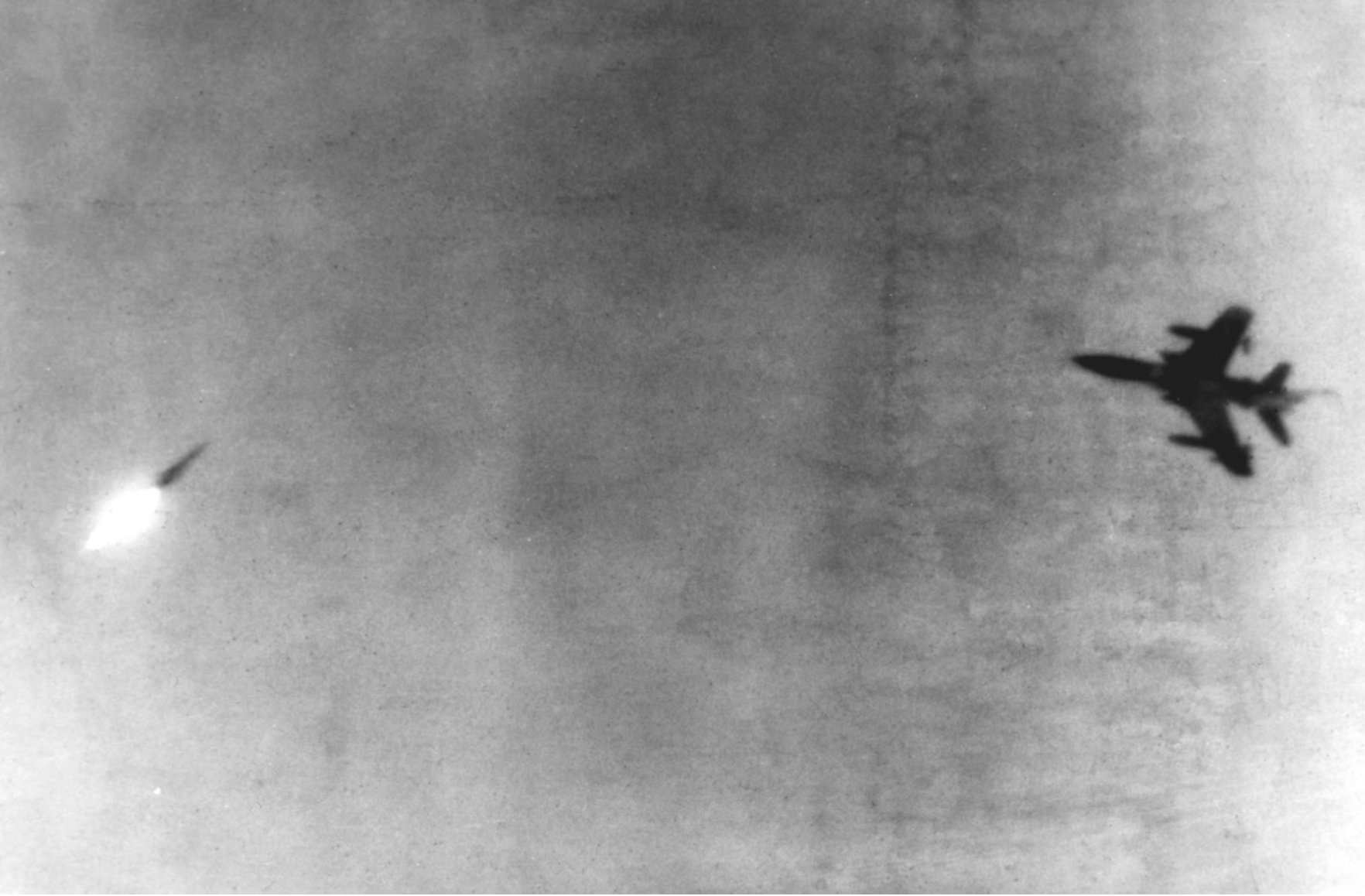

When a Soviet-made, SA-2 surface-to-air-missile (SAM) was launched at an F-100F Wild Weasel fighter jet, the atmosphere in the cockpit was surprisingly calm for the danger posed by the thirty-five foot long missile closing in on to the plane at three and a half times the speed of sound. Detecting the launch with the “oh shi— light”, the Electronics Warfare Officer would call for his pilot to “take it down” in the general direction of the launch, searching for black smoke to indicate the exact location of the launch site. When found, the pilot would roll the aircraft over and dive directly towards the missile, pushing the throttle to full power. Locating the speeding telephone pole sized missile, the pilot would hurtle the plane towards it, pulling out of the steep dive a half second before the two hundred and eighty eight pound warhead would have otherwise slammed into the jet at supersonic speeds. If the evasive maneuver was successful, the aircraft would then proceed to strafe the heavily camouflaged missile site to destroy it.

This was a textbook mission. Not all missions bore such results for the US Air Force crews who flew them. Charged with protecting strike packages of F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bombers, the Weasels were be the “first in” and “last out” in a mission. As Wild Weasel and Medal of Honor recipient Leo Thorsness recalls, “The strike pilots had a fixed target dropped their bombs, and they’d be maybe two minutes. We’d be trolling around in there for maybe twenty minutes.” The first Weasel crews had less that a fifty percent survival rate. Indeed losses only worsened with the arrival of the second squadron of Weasels. As one pilot recalls, “We arrived [at Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base] on the Fourth of July in Sixty-Six. We had eight aircrews and six airplanes. Forty-five days later we had no airplanes, and of our sixteen people, four had been killed, two were prisoners of war, three had been wounded two of them had wounds so serious they had to go back to the states and one fellow had quit.” From the perspective of airmen in theater, this tactical situation and their losses might have been avoided. Pilots had watched as the North Vietnamese gradually built their air defense umbrella, but air strikes were forbidden especially on surface to air missile sites because of restrictions issued from political authorities who oversaw the war from Washington DC. These political restrictions seemed folly to the pilots fighting every day, who recoiled at the waste of aircraft, men, and prestige, but they were a necessary and just part of a global containment strategy to stop communism while avoiding global conflict.

Beginning in 1962 with the deployment of 3,000 US Military advisors to assist the South Vietnamese Armed Forces in combating the Viet Cong insurgency, the war over the skies of Vietnam began modestly. Soon, without permission, American pilots began to fly reconnaissance and ground support missions, pretending to be South Vietnamese Air Force pilots. This low level of US engagement corresponded to the limited guerrilla warfare the Viet Cong waged against the South Vietnamese government to undermine its control. In 1963, with increases in the guerrilla war around Saigon and in the Mekong Delta, the United States began to escalate its involvement by deploying aircraft to support the South Vietnamese Army. But, support was small-scale and tactical in nature, and the United States refrained from attacking strategic targets in North Vietnam.

After the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, America began to bomb strategic targets in North Vietnam. With escalation into the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign, America’s policy makers attempted to slow the flow of material support to the Viet Cong and thus bring a Korean Conflict type conclusion. Initially planned for several weeks, the operation continued when the North Vietnamese would not yield not Rolling Thunder’s pressure. Fours years later, when Rolling Thunder concluded, it would be America that yielded unable to force the desired result militarily without the risk of broadening the war. Fourteen hundred American pilots and over 50,000 Vietnamese would be dead.

Defended by only 1,500 Anti-Aircraft-Artillery (Triple-A) guns at the start of Rolling Thunder, North Vietnam was poorly prepared for the onslaught of the United States Air Force and Navy. Initially, US Air Superiority over the skies of North Vietnam proceeded as planned and losses were acceptable in the context of similar, historical efforts.

Once the United States had committed itself to Rolling Thunder, the Soviet Union began to increase the quantity and sophistication of the armaments it gave to the North Vietnamese including the SA-2 to counter American efforts. While not considered accurate above 30,000 feet, the SA-2 changed the nature of the air war, forcing bombers higher and thus decreasing the accuracy of their strikes, or lower and into a newly built up mass of Triple-A. Even when flying at higher altitudes where SAMs were less effective, aircraft were often forced to drop their bombs prematurely to conduct evasive maneuvers. As one pilot notes, “a SAM is what got Gary Powers in the U2. The missile was effective, it could reach you at most altitudes you flew at.” While only eleven of the 180 SAMs fired in 1965 destroyed aircraft, the sophistication and lethality of the missiles intimidated pilots and influenced mission planning. This fear became so deeply ingrained that some predicted SAMs would be “the death of the flying Air Force”

First detected under construction on April 5, 1965, by a U2, the deployment of fifty-six SAM sites was closely documented and monitored by the US Military. Banned from attacking these sites out of political worry that Soviet advisors might be present to oversee construction, pilots helplessly watched the sites become operational over the next three months. Indeed, the unloading of numerous SAMs and other armaments in the port of Haiphong was also observed, and again strikes were banned out of fear of escalating the Cold War. As one enraged pilot recalls; “They photographed [the missiles] everyday being loaded onto trucks and hauled out to the countryside. They photographed them being set up in the jungle… we could have knocked them out right then, but that was never the case. We had to wait until they were operational to shoot us down and then our leader [Secretary of Defense] McNamara would allow us to hit one site.” The seeds of dissent among pilots were sown during this early phase of Rolling Thunder when political concerns predominated military ones.

While the US Air Force and Navy had been aware of the threat posed by the SA-2 since the mid-1950s, no strategy had been developed to counter the threat. When the US Air Force (USAF) suffered its first combat loss to a SAM over North Vietnam on July 24, 1965, the Air Force moved to establish a committee to counter the threat. Under the command of the Air Force’s Chief of Staff General John P. McConnell, the Dempster Committee recommended the development of a squadron of fighters with special electronics to seek and destroy SAM sites with missiles capable of homing onto SAM radar systems. These recommendations began to be executed in a new program known as Project Wild Weasel.

While this committee was underway, something had to be done about the immediate SAM problem facing aviators over North Vietnam. After the initial loss, McNamara took to the New York Times to announce that the United States would destroy the offending missile site by the end of the week. The next day, orders for Operation Iron Hand arrived. A strike force was to be assembled to attack the SAM site under very specific mission criteria including: altitude, airspeed, and ordnance. At Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base, pilots were upset when they saw the “idiotic” specificity of the orders. Reflecting on the mission, pilot Billy Sparks described the orders as “the absolute most incredible bunch of crap imaginable,” noting that his “grandmother knew more about targeting than” to fly only fifty feet above the ground at half the usual speed of a bombing run. With pilots upset by what they perceived to be “suicide orders”, their commanding officer phoned headquarters in Saigon to request changes to mission parameters but this request was denied.

On July 27, 1965, sixty-four aircraft were sent to eliminate the SAM site. Fifty-six returned. As one pilot remembers: “There was no missile equipment anywhere in the area. The North Vietnamese had taken telephone poles, painted them white, and propped them up with pine trees they had cut down to make it look like a missile site.” Instead, hundreds of guns of all caliber greeted the strike force as it rolled slowly into a bombing run of a nonexistent target.

Iron Hand undermined the trust pilots had in their chain of command. Angered by McNamara’s New York Times article detailing the location of the site to be struck and also by his other comments regarding a surplus of pilots in theater, aircrews responded with gallows humor: perhaps their numbers could be reduced by announcing the location of targets ahead of time more often. Pilots became even more enraged when they discovered the orders for the strike had been passed through command in Saigon where “[all information made its way to] Hanoi in hours”. In his 2013 memoir, Billy Sparks considered the Department of Defense’s judgment dereliction of duty at best and treason at worse given that they were aware of the leaks in Saigon. “I promised myself that I would never, ever allow anyone, regardless of rank, to waste so many folk” said Sparks. “I owed it to the people I flew with to take better care of them than that”. Beyond questioning the military qualities of orders given, front line pilots often felt that their efforts were subservient to the career advancement of officers above them. “No one ever paid any penalty for those names that went on the wall [because of Iron Hand]” Sparks lamented.

In the wake of Iron Hand and growing fears over the SAM threat, the head of Project Wild Weasel, Brigadier General Kenneth Dempster quickly organized meetings between the military and defense contractors to pursue creating a squadron with a radar homing and warning (RHAW) electronics system. When Applied Technology Inc. came forward with the AN/ APR-26 electronics system capable of detecting SAM radar frequencies, the Air Force negotiated a deal to use the technology in hours, and Applied Technology had the adopted for the an aircraft in just thirty days. During testing, it soon became apparent that the pilot would not be able to mange the complicated electronics system on his own and that the mission would require a second crewman. This prompted the addition of an Electronic Warfare Officer (EWO) whose primary duty was to manage the system.

Recruiting the “best and brightest” the Air Force had to offer, pilots were required to have at least two thousand flight hours and EWOs were selected based upon their skills and experience with sophisticated electronics in aircraft such as the B-52. As pilot Mike Gilroy described, Weasels additionally required an arrogance that the job would “not [be] too tough” and a feeling of being “bulletproof”

Because of the danger of the Weasel mission, pilots and EWOs were allowed to select one another over cocktails and often had mock weddings. As Billy Sparks notes; “the joke went that you were together for a hundred missions or death to you part.” Forming powerful bonds, pilot and EWOs (affectionately called “Bears”) often developed their own means of communication in the cockpit alerting one another of threats and other pertinent information. So close was the bond between pilot and EWO that one Weasel remembers that he’d “rather have someone mess with [his] toothbrush then to mess with [his] bear [because his] bear was the most important thing in the world to [him] at the time and for very good reason. “

Beginning their training in October of 1965 at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, the initial Weasels’ training was accelerated and highly expedited given the hot war in Vietnam. Focused on destroying sites before strikes and suppressing SAMs while aircraft were in the vicinity of the target, the Weasels developed tactics to “make the SAM drivers nervous and shaky”. In an Iron Hand mission, Weasels would fly in front of a strike force to entice SAM operators to engage them so that they could attack the sites. With the sites neutralized, the strike force could continue on their mission with less risk. As a Wild Weasel training aid mentions, “the actual destruction of SA-2 sites [was] normally of secondary importance in the suppression role and [would] not normally be carried out unless a particular site [could] be destroyed without sacrificing the protective suppression the strike force [required] from other threatening sites.” Nicknamed “dancing with the SAMs” by pilots due to the sudden evasive maneuvers required to dodge the speeding missiles, the specifics of missions were at first laughable. In one briefing, when EWO Jack Donovan first understood the scope of his mission he exclaimed: “You want me to fly in the back of a little tiny fighter aircraft with a crazy fighter pilot who thinks he’s invincible, home in on a SAM site in North Vietnam, and shoot it before it shoots me, you gotta be shittin’ me!” Donovan’s statement resonated with many a Weasel as “you gotta be shittin’ me” soon became an unofficial motto, appearing on patches and planes as “YGBSM”.

Arriving in Korat just a month after starting their training, the eight initial pilot-EWO teams endured a week of briefings on rules of engagement. Having already been banned from attacking any SAM site that had not fired, the list also included MiG fighters at their airbases, dams, power grids and other strategic targets. One Weasel complained that “we could have cleared just about all of the radars in the North with very little trouble [and could have] blind(ed) the air defense system of the [North Vietnamese] with very little cost and no change to the number of [missions] flown” by having the planes already conducting strikes strafe radars on their return flights.

Flying their first mission on December 1, 1965, the Weasels destroyed nine SAM sites but found the F-100F (Wild Weasel I) inadequate for the mission due to its slow speed and low tech electronics fit. Equipped with the AN/APR-26 radar homing and warning receiver (RHAW) system, but with no dedicated anti-radar missile, it relied on strafing and bombing to destroy targets. While their aggressive tactics paid off, the initial Weasel crews experienced heavy losses during their first weeks in theater — losing three planes. In response to the inadequacy of the F-100F, the Air Force deployed the next generation of Wild Weasel aircraft (Wild Weasel III) based on the F-105 Thunderchief airframe. Used in seventy-five percent of the strikes against North Vietnamese targets, the F-105 had proven itself a versatile and capable platform. Nicknamed “Thud” for the sound pilots sardonically associated with its crashes, F-105 pilots held their mounts in high regard despite the cynicism they felt for their missions. Famous for its low level high speed, and its rugged construction, pilot Robert Dorrough raves, “The F-105 is the greatest plane I’ve ever flown, [because] it can take a lot of hits and still go on”. When the Wild Weasel III F-105s were deployed to Thai air bases, they represented a significant step forward: with a better electronics fit (Applied Technology’s APR-35/37) and, more importantly, a weapon dedicated to the destruction of SAM radars.

The Shrike was the world’s first dedicated anti-radiation missile. Based upon the AIM-7 Sparrow air-air missile, the Shrike incorporated a new guidance system which allowed it to home onto radar systems such as the Fan Song that was used with the SA-2. As Weasel Don Kilgus recalls, the Shrike changed the nature of the mission because it allowed the Weasels to attack SAM sites from afar and with a greater probability of disabling the target. The Shrike was not without limitations. Relatively short ranged and with a small warhead, it required pilots to expose themselves to the very SAM they wanted to destroy. Additionally, the Shrike lacked the ability to remember the location of an emitted radar signal. When first deployed, the Shrike was devastating. Soon, though, North Vietnamese radar operators developed tactics to minimize the missile’s effectiveness. In response, American tactics and technology evolved. So continued a tug-of-war between Wild Weasels and SAM operators for control of the skies over North Vietnam.

Even as the battle in the air raged on, pilots felt continual strain regarding targets and tactics for waging their part of the conflict. Disobedience of orders — even in cases of self defense — often resulted in a court martial for a pilot and EWO. For example, if an F-105 crew attacked a new SAM site that had fired at their aircraft while it was egressing a mission, it would be considered a violation of the strict rules of engagement and a court martial could be ordered. One Weasel recalled Lyndon Johnson pronouncing, “them boys over there can’t bomb an outhouse without my say-so.” Sentiments like these fostered the notion that America fought the war in Vietnam only half-heartedly — and ignored the broader global political context in which the war was fought.

The geopolitical context of the war dictated a measured response to perceived communist aggressions. Just three years prior, the world had been almost driven to nuclear holocaust because of the Cuban Missile crisis, and America’s strategic forces remained on high alert. For example, during Operation Chrome Dome, B-52 strategic bombers carrying nuclear weapons remained airborne continuously — flying routes over the arctic from 1961 through the entirety of Rolling Thunder. Because of the simmering Cold War, Johnson and McNamara favored restraint over a more aggressive approach prosecuting the war in Vietnam and specifically to combat the SAM threat.

A visceral hatred of Johnson and McNamara grew as Rolling Thunder progressed. When a New York Times article titled “How Johnson Makes Foreign Policy” was published, pilots mocked the breakfast meetings over which targets were selected and policy decisions were made. As Billy Sparks lamented, “The major problem with Rolling Thunder from day one was that the targets we were assigned made zero sense … I think my mother could have done better.” Indeed, the command at Korat and Takhli had given the Defense Department an ordered list of 207 targets within North Vietnam that were of strategic importance but the commanders were not given the freedom to ever update the list as conditions changed. Political leadership also favored bombing the lowest priority targets first — the exact opposite of what the military leadership had requested.

The waste pilots experienced was best seen in a typical raid to destroy a supply dump or truck convoy. To execute their mission, the Air Force would deploy twelve F-4s to bomb the target, four F-4s to provide protection from MiG fighters, eight Wild Weasels to suppress the SAMs, and an RF-4 reconnaissance aircraft to photograph the site for damage assessment. These strikes were often unsuccessful as the Viet Cong operated in small groups in the dense jungle. As one general suggested, air missions to “bomb [the North Vietnamese] into the stone age” were largely unsuccessful because “they were in the stone age, what were we going to bomb them back to?” On one mission, the Air Force bombed a choke point in the mountains known as the Mugai Pass. The strike force consisted of more than thirty planes dropping six hundred tons of bombs at a cost of twenty-one millions dollars. Though successful in closing the path temporarily, over the next two days 150,000 North Vietnamese labored and reopened the pass. As one Thud pilot remarked, “We take a 20 million dollar fighter and launch it against a four dollar bicycle and get shot down doing it. That’s pretty insane. And that shows you a lot of what the F-105 and others were up against — it’s hard — you can’t win that kind of war.” A lack of ordnance too, often compelled fighters capable of carrying eight bombs to fly with only one — further decreasing the “efficiency” of the war.

For many F-105 crews, reaching the magic hundred missions needed to complete their tour of duty seemed a nearly impossible task. For those pilots not immediately killed after being hit by a SAM, death still remained an imminent threat. As one pilot remembers hearing on Hanoi radio of one of his friends downed that day, “angry villagers had run out and killed the pilot. They were so mad that with their pitchforks and shovels, and sieves and all that they had punctured the man and killed him.” Death often seemed a better option to those captured and brought to the Hỏa Lò Prison in Hanoi. Acrimoniously nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton”, prisoners were malnourished, tortured and sometimes placed in solitary confinement for years.

All the danger posed by the mission failed to dissuade some pilots from signing up for an additional tour of 100 missions. As Tom Cushenberry explained, “I had [signed up for another hundred missions because] I still was a soldier and I felt that if they [were] gonna keep on doing [the missions] then they needed someone with my experience … somewhere in the mix over there [so that] I may make a difference to somebody.” Continuing, Cushenberry commented on the success of his mission and how he wasn’t going back to help the effort “because there was no effort.” Even Billy Sparks — constant cynic and critic — returned to Vietnam as a Weasel after serving as a strike force pilot. He calls his time in Southeast Asia, “the singe most important thing I have ever done” in his memoir.

While pilot’s motivations can never be know for certain, many returned for unexpected reasons. “I just got bored” shrugs Larry Waller, home after completing two hundred missions. Had Air Force regulations permitted a third tour, he would have volunteered to return. In the words of General Patton, “compared to war, all other forms of human endeavor shrink to insignificance.” For some, war is, “a potent …. addiction” that often kills its victims. If considering the role of these pilots in the context of jus in bello (justice in war), it must also be considered that a number of pilots not only volunteered for their service and initial tour, but also to return to a war fully aware of its inconsistencies and ambiguities.

With the end of Rolling Thunder on November 1, 1968, Weasel involvement in Vietnam too began to wind down. While most Weasels returned to the United States, the remaining ones were consolidated into the 6010th Wild Weasel Squadron at Korat. Protecting reconnaissance planes that flew missions into 1972, the Weasels saw little action. With the commencement of Operations Linebacker and Linebacker II in 1972, the Weasels once again took to the skies to protect convoys of B-52 bombers as they proceeded north to bomb Hanoi. Armed with an improved anti-radiation missile (the Standard ARM) and now well trained in anti-SAM tactics, the Weasels performed skillfully, successfully able to suppress the more advanced Soviet SA-3 system without losing a single aircraft. Helping to ensure the success of the Linebacker operations, the Weasels helped bring North Vietnam back to negotiations at the Paris Peace talks just eleven days after the start of Linebacker II.

Throughout their mission, Weasels and strike pilots wondered what they were doing, and if their losses were in vain. As one Weasel pined on his role, “I felt that there was no reason for dying for a country that didn’t care and had no intention of ever winning the war.” Anger, fear, and a resentment of the commanders who had placed them into their role filled most Weasels’ hearts as they returned home. Though grappling with a perceived meaningless destruction of their friends, many Weasels remained silent in their views of their commanders and very few cried out against them openly in the press.

While the loss the Weasel endured were immense, and some of those losses were not required to punish the North Vietnamese for their support of the Viet Cong, the restraint the US political leadership used in the air war had implications across the globe. Through the latter sixties and into the seventies, Soviet-American relations had become more amicable and the superpowers began to sign treaties such as the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT) which limited the number of nuclear weapons the powers could hold and governed how new nuclear systems could be developed in the future. This rapprochement between superpowers was known as détente and it peaked in the mid-1970s.

On July 17, 1975, 229 kilometers above the Earth, an Apollo and Soyuz capsule docked with one another. The astronauts shook hands, exchanged gifts, shared a meal, and flew home. Détente was at its height and Soviet-American relations had reached a new level of cooperation. As President Nixon emphasized “Détente [did] not mean the end of danger … [and it was] not the same as lasting peace” but the world had become a much safer place because of it. The sacrifices of those who fought in Vietnam not only checked Communist aggression for a long time, but the restraint that they showed enabled the first thaws in the Cold War. Hundreds of men served as Wild Weasels during the Vietnam War. Seventy-two were shot down. Nineteen endured the horrors of captivity. And thirty-three never came home alive. Many veterans live with agonizing, horrific memories of their time as Wild Weasels. While millions of lives across the world had been saved by the tremendous sacrifices Weasels and others had made, as the Weasels remained an entirely officer and volunteer force throughout the war, it can not be said that the United States political powers at be prosecuted a war that violated ethics of jus in bello by restraining their pilots’ ability to take preventative measures against future threats and to execute the mission they believed they were there to carry out.

Standing invitation (inspired by Patio11 who also has some good tips on how to approach this): if you want to talk about hard tech or systems, I want to talk to you.

My email is my full name at gmail.com.

- I read every email and will almost always reply.

- I like reading things you’ve written.

- I go to conferences to meet people like you.

- Meetings outside of conferences are tougher to fit with my schedule - let’s chat over email first. Specificity and being concise makes it easy for me to reply :)