Delta Wings & Supersonic Dreams

09 Jun 2025I wrote the following essay as a school research project into the Cold-War race for civil supersonic flight. In those times, Concorde’s slender delta wing came to symbolize industrial ambition, national pride, and, ultimately, the crushing economics of the luxury high speed travel against the egalitarian jumbo jet.

The first supersonic age ended in defeat when Concorde retired in 2003, but a few months ago, Boom Supersonic’s XB-1 demonstrator began a new era. Built in a Colorado warehouse rather than a state-owned hangar, Boom built the first privately funded civil supersonic aircraft, and broke the sound barrier in the quietest way ever recorded.

The story that follows captures the drama of that first supersonic age; may it also offer context, and a bit of propulsion, as we watch the second one taxi toward the threshold.

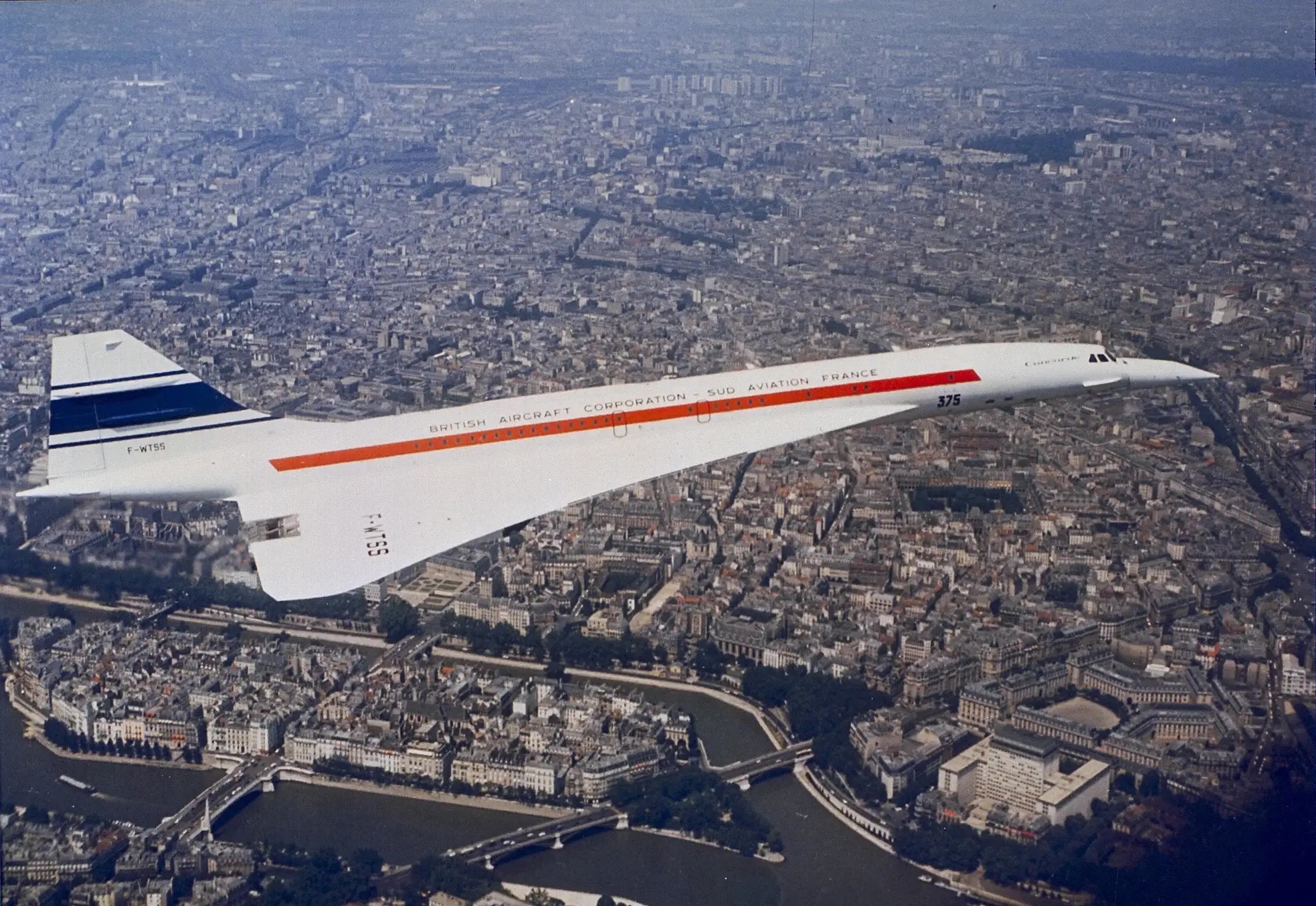

Slowly backed from her hanger in the southern French city of Toulouse, fresh white paint across her slim body and slender delta wing glistening in the late afternoon sun, Concorde 001 was ready. The names of her creators BAC (British Aircraft Corporation) and Sud Aviation France above the slim red cheat line that ran the length of her fuselage, Concorde stood in front of the world’s media for the first time on the afternoon of March 2, 1969. After checks, double checks, and checks one last time, Concorde slowly pivoted onto runway 33L, 7 years after the signing of her development treaty, 10 times over her original budget, and with builders unsure of her prospects considering Boeing’s new 747 jumbo jet had flown less than a month earlier in Seattle.

Firing her four reheats two at a time and rolling down the runway to the delight of spinning newsreels, Concorde effortlessly lifted into the sky for her inaugural flight. Nose and landing gear extended through the duration of her “faultless” (as described by the exuberant French press) 27 minute maiden flight above the French countryside, Concorde effortlessly glided back onto the runway, the small white drag chute she carried for testing artfully following her down the runway.

Emerging from Concorde and hustling down a movable staircase to the applause of Sud and BAC executives, Pilot Andre Turcat entered the adjacent terminal to address the waiting media throng. “The big bird flies.. and it flies pretty well.” After 7 years of work, a prototype had flown. Closely following the first flight of the Soviet supersonic transport (SST), which had flown just three months prior, the Anglo-French effort now definitively led the SST program of the United States. Despite its ambition and disdain for its Anglo-French competition the United States was nowhere near its first flight, and, indeed, never would be.

The United States’ SST program began with an inspiring launch speech from President Kennedy at the US Air Force Academy’s 1963 commencement. Seeking to beat Concorde in every metric, Boeing had entered an overambitious sweep-wing design into the bidding process and the government chose it over more moderate alternatives. With a passenger capacity and maximum speed nearly twice that of Concorde and an all-titanium airframe, the United States entered the race to build a commercial SST, planning to dominate the anticipated global market as it had in subsonic commercial aviation. After eight years of development, and $1.8 billion, Congress stopped funding the program in December 1970 and its principal developer Boeing subsequently disowned the project - failing even to produce a prototype.

Since the introduction of commercial aircraft, each successive generation had flown higher and traveled faster. Built in the heat of the Cold War, the next, supersonic generation of commercial aircraft would be heavily influenced by the clash of communism and capitalism. With Chuck Yeager shattering the sound barrier in the bright, orange Bell X-1 “Glamorous Glennis,” in 1947, and the Soviets breaking the Mach (768mph at sea level) barrier a year later, the race for speed began, powered not only by rocket engines, but by the quest for ideological superiority.

After this initial catalysis, however, the West turned inward. Soviet civil aircraft rarely flew in Western airspace, and with a substantial wall preventing inter-bloc commerce, the Soviet Union’s SST endeavor was not a threat to Western aircraft manufacturers - just to the pride of the world’s capitalists. The Soviets had started the race, and they continued to run, far ahead, reveling in the propaganda and inferred superiority their achievement brought them, but the real fight was behind them, between the United States and the Anglo-French. Britain had initially led jet-powered civil aviation, but after the disastrous de Havilland Comet, its industry lacked in prestige and sophistication. Seeking redemption, Britain embraced the SST, partnering with the French to challenge the United States’ global dominance in civil aviation.

Worried about Anglo-French collaboration, the United States launched its own SST program. Had American and European projects matured quickly and inexpensively, the story of the SST might well have ended differently. With billions poured into the project on both sides of the Atlantic, and program delays mounting, public opinion began to shift against the planes. The United States, with plans shifting towards massive, cost effective aircraft such as the Boeing 747 jumbo-jet, dropped from the SST race. Britain and France, with aircraft industries in decline and no alternative plans, felt they had to push to lead commercial aviation with their auspiciously launched Concorde.

Led by prominent Welsh aeronautical engineer Morien Morgan, Britain began a study of the viability of supersonic commercial aircraft at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in 1954. After Sputnik’s launch in 1957, development began in earnest, through the Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee (STAC) which had been established a year prior through the Ministry of Supply. As Morgan summarized in successive STAC meetings, building a supersonic transport was not only a matter of national pride, but a matter of reviving Britain’s troubled aircraft industry. In 1952, Britain had been the first nation to launch a commercial jet with the de Havilland DH. 106 Comet. It was initially a wild success. During its first year, Comet flew 28,000 passengers 104.6 million miles across the world and de Havilland even took orders from the United States’ flagship carrier Pan Am. Beneath this success, however, lay myriad deadly design flaws. First, in October, a Comet ran off the runway in Rome because of a broken piece of landing gear. The 35 passengers and 8 crew members of that flight were spared, but just five months later, in April 1953, a Sydney-bound Comet crashed on takeoff- killing all 43 souls. Comet’s wings were poorly designed, but subtle modifications to the problematic leading edges, and more instruction for pilots restored Comet’s airworthiness and it hurried back into the sky, deprived of her perfect safety record and with a little bit less prestige.

Less than a month after the April crash, and exactly a year after Comet’s May 2, 1952 inaugural flight, disaster stuck again. Climbing above an afternoon thunderstorm on a flight out of Calcutta, India, a Comet disintegrated. Weather was thought to be the probable cause of that disaster. As the Times of London declared on May 4, 1953, 2 days after the crash the plane was “knocked down by the tempest.” Comet and her promising leap into the future for civil aviation and the British aircraft industry was in danger. The death blow that brought Comet and everything behind her back to Earth, was about to come.

Seven months after the May crash, in January of 1954, a flight from Rome to London fell out of the sky on a cloudless winter day over Italy’s Tyrrhenian Sea near Elba. Hurrying to the debris field, fishermen pulled suitcases, pieces of fuselage, bodies, from the water. Any chance of redemption for Comet was lost. Initial reactions to this crash were mixed. Headlines declaring the crash sabotage, jumbled the world’s thoughts, as the story ran as far from the British Isles as Australia. An investigation commenced, but in a time before flight data recorders and with the plane broken up and at the bottom of the ocean, all Comets returned to service two months thereafter.

Less than a month after Comet’s second return to service, tragedy struck again near Naples, Italy when another plane fell from the sky. This was the end. Though Comet was to return to service in October, 1955 before ultimately retiring in November, 1967, it had been grounded for over a year while an extensive operation by the Royal Navy retrieved one of the planes from the sea floor, and an intense investigation revealed metal fatigue from constant pressurization to be the deadly weakness. Though first to introduce a commercial jet, Britain with its Comet, had lost the all too important battles of prestige, and safety to the American commercial jets that followed.

With Boeing’s 707, Douglas’ DC-8, and other American commercial jets over 80 percent of the civil aircraft flown in the West, the British had lost the advantage, and ultimately the ability to compete in the jet market. As Permanent UK Aviation Secretary Sir Cyril Musgrave reflected, “All the major airlines were buying the 707 or the DC-8 and there was no point in developing another subsonic plane. We felt we had to go above the speed of sound, or leave [the market].” Minister of Aviation Duncan Sandys agreed with Musgrave noting that, “If we are not in the supersonic aircraft business, then it’s only a matter of time before the whole British aircraft industry packs it in.” Stressing that supersonic travel was, “obviously the thing of the future,” and that staying out of the race would be the most expensive thing the country could do because, “If we miss this generation of aircraft we shall never catch up.” Musgrave concluded that, “[though] it may not pay, we cannot afford to stay out.” This sentiment of necessity began to flow through the project, and citizens to politicians began to view the construction of a supersonic jet as more an issue of pride and desperation than of practicality.

For Britain, building a supersonic transport was seen not only as a path to national prestige, but also as a path to redemption, for its failing aircraft industry. Each successive generation of commercial aircraft had improved on the previous generation in speed, and the general consensus was that this trend would continue through the sound barrier. Postulating that “in two or three decades… the bulk of long distance passenger travel will be at supersonic speeds,” Morien Morgan, now Deputy Controller of Aircraft Research and Development, firmly concluded in an October 1960 meeting that “if Britain is to retain its position as a leading aeronautical power, we cannot let ourselves be edged right out of the supersonic transport field by America and Russia.” Building a supersonic aircraft had great stakes for Britain, and the political and technical bureaucracy were lining up to support it.

For Morgan, technological knowhow and developmental knowledge was the most important aspect of a supersonic transport project. Noting that, “Since this country’s future will depend on the quality of its technological products and since its scientific manpower and resources are less than those of the USA, and the USSR, it is important that a reasonable proportion of such resources are deployed on products which maintain our technical reputation at a high level. “While knowledge and display of technical prowess would certainly improve Britain’s national prestige, in order to convince commercial airlines to purchase the SST, its commercial viability would need to be shown. With an initial development budget between £165-265 million, and with operating costs projected to be five times that of a conventional aircraft, aircraft manufacturers doubted the pragmatism of committing so many resources to such a high risk project.

In addition to his conviction that Britain must build a supersonic aircraft in order to remain competitive, Morgan asserted the UK should act as soon as possible because it had a “two or three-year lead on the [competition] in hard thought and supporting research on supersonic transport problems. “Continuing, he suggested that to most practically use this advantage to produce a jet quickly, a mid-sized supersonic jet capable of about Mach 2 (1200mph) would be most reasonable. Simultaneously predicting the high cost of a supersonic endeavor but cognizant that “not to embark upon such a project would be tantamount to the exclusion of this country from the field of advanced civil aircraft design,” Britain began the search for a partner.

Across the English Channel, France faced similar issues with its aircraft industry. In a wave of early 1950s nationalism, President Charles de Gaulle had pushed his state’s leading aircraft manufacturer, Sud Aviation, to develop a jet of its own. Flying for the first time on May 27, 1955, the SE 210 Caravelle was a minor success, selling 282 jets to airlines across the world including in America, but ultimately failed to compete with the dominant Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. With the example of the Caravelle in mind, France, like Britain, was determined to produce an SST to counter the “American Challenge” and to ignite a French and broader European aircraft industry that would reduce the United States’ utter dominance of the civil aviation market.

With Britain and France independently concluding that a mid-range, Mach 2 jet with a slender delta wing design would be the ideal configuration for the first SST, the countries seemed ideal partners for one another. For Britain, working closely with the French could gain them access to the newly formed European Economic Community and its Common Market of free trade and simultaneously reduce the amount of time needed to settle on an SST design, and the transit time large components would need to travel between countries. With these advantages of Anglo-French cooperation, however, came opportunity cost. America led the world in civil subsonic jet aircraft and, in preparation for the supersonic era, its engineers had amassed a collective 100 years working on supersonic problems, and had conducted thousands of crucial hours in wind tunnel testing. Indeed, on trips to the United States, numerous members from the RAE had been thoroughly impressed by US knowledge of supersonic transport and advocated for an Anglo-American coalition.

Initially pursuing an Anglo-French coalition, Minister of Aviation Sandys met with officials from the French Air Ministry in February of 1960. Continuing these meetings, Sandys began to believe his French counterpart General Jean Gerard lacked interest in the project, declaring at an April 1960 meeting that: “If we see no possibility of quick collaboration with France, we shall turn to the USA.” Because of this inferred disinterest, Britain banked away from France and headed back to the United States.

Frustrated by the French, the British Cabinet, led by the Chancellor of Exchequer, Derick Heathcoat-Amory, Minister of Defense Harold Watkinson, and Minister of Aviation Sandys convened in July 1960 to establish a plan. Concluding that they must “create a negotiating position” for the United Kingdom to “secure the United States collaboration” the attempt to collaborate with the United States began.

Meetings with FAA Administrator Elwood Quesada in September 1960, initially seemed promising. Quesada had agreed with Sandys that collaboration would be mutually beneficial, but his suggestion that the United States should build the plane’s airframe and the United Kingdom provide the engines was off-putting for the British. They wanted to be partners — not suppliers of components. Continuing discussion through the Civil Air Ataché Roy MacGregor at the British Embassy in Washington, a year passed with no progress. The United States didn’t seem interested in anything beyond banter. As the talks wore on, Quesada epitomized the skeptical view of the Eisenhower administration if supersonic aircraft had any chance of being commercially successful, they would take at least a decade for airlines’ to begin actively making new investments to replace their new fleets of subsonic jet aircraft. MacGregor and the other British diplomats slowly grew annoyed at this rhetoric. In November 1961, an unknown British diplomat issued the same ultimatum given to France the previous year: if she could not secure collaboration with the United States soon, the British would partner with the French. The stakes were high, and the British wouldn’t wait for a partner — even if that meant moving forward alone.

With the United States “hardening against collaboration,” and bent on producing a more ambitious Mach 3 (1800mph) jet with twice the capacity of the their design, the British flopped back towards the French. Eventually finding common ground, the two countries planted the seeds of cooperation with the signing of an agreement called “The Development and Production of a Civil Supersonic Transport Aircraft” on November 29, 1962. Committing themselves to build the mid-sized, slender delta plan that their designers had been advocating, the British insisted the treaty have the same scope of an international treaty, ensuring the French would continue collaboration. Committing £28 million a year each, for a total estimated budget of £224 million per country, the program began — its managers oblivious to the technical challenges and resulting budgetary explosion that would soon dominate the efforts of both nations.

Deciding to split work on the airframe between the British Aircraft Corporation and Sud Aviation and work on the engines to Bristol-Siddeley and SNECMA (National Company for the Design and Construction of Aviation Engines), Britain and France began as equal partners: sharing costs, technology, and encouragement. Political strife, however, soon threatened the very existence of the project.

In joining with France, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had hoped to demonstrate his country’s commitment to Europe to his counterpart, President Charles de Gaulle. With his close historical relationship with the United States, and with France positioning itself to be Europe’s new economic powerhouse, Macmillan felt that engaging with the French on such an ambitious project could help to ease relations and help Britain to gain access to the newly formed European Economic Community and its “Common Market” of free trade.

On January 14, 1963, de Gaulle crushed British aspirations to join the Common Market at a crowded press conference at Paris’ Elysse Palace. In a prolix answer, de Gaulle asserted that English entrance would eventually lead to American entrance and thus, “American dependency and direction” that would “absorb the European Community” and subjugate the national identities of Europeans. Having effectively vetoed any British attempt to join the Common Market, de Gaulle then brilliantly renewed both countries commitment to developing the Concorde, calling for the maintenance of continued close relations with Britain in “every domain.” British resolve to continue work had been weakened, but, searching for an entrance for its industry back into civil aviation, it decided to continue the collaboration.

Assuming the British prime ministership in the midst of an economic crisis in early 1964, “honest broker” Harold Wilson began a futile attempt to maneuver Britain out of its treaty obligations to continue supporting the ballooning costs of Concorde. With the strength of an international treaty, however, leaving the agreement was not an option. With the right to pursue an international civil suit at the Hague, Britain could be forced to continue paying for development. As Wilson noted:

Had we unilaterally denounced the treaty, we were told, we could have been taken to the International Court, where there would have been little doubt that it would have found against us. This would have meant that the French could then have gone ahead with the project no matter what the cost, giving us no benefit from the research or the ultimate product. But the court would almost certainly have ruled that we should be responsible for half the cost. At that time, half the cost was estimated — greatly underestimated as it turns out — at 190 million pounds. This we should have had to pay with nothing to show for it.

Maneuvering through Assistant Administrator for International Aviation Affairs Raymond B. Mallory, the British learned that the French were set on continuing, and that they would be content to do so alone provided with sufficient capital and a good engine — sourced from the United States or Britain. Britain was stuck in the cockpit and hurtling down the runway.

As the project continued, costs continued to soar. From an estimated $400 million total in 1965, through reprojections of, £770 million, £1.26 billion, £1.75 billion, £2.63 billion, Concorde’s cost ultimately steeled at a staggering £3.25 billion (a staggering £24.64 billion in 2016 adjusted pounds). After another £0.85 billion in production costs for the 16 Concordes produced, Britain and France each had a £2.05 billion (£15.54 billion in 2016) tab.

Across the Atlantic, the United States faced a similar budgetary progression. By 1971, the nation crossed the billion dollar mark in spending and the costs were beginning to be too much. Significant technical challenge in confronting the exponential growth of drag as a plane increased in speed, and working with the titanium necessary to help the Boeing design exceed 3 times the speed of sound had slowed the project to a standstill. Technical and budget issues, together with the new public and environmental opposition to the Boeing 2707 eventually would see the aircraft from even making it to the tarmac.

Similar to the Apollo Project, the US SST effort began as another glistening beacon from Camelot. Climbing a stage at the United States Air Force Academy’s Falcon Field eight years earlier in June, 1963 to give the commencement address, President Kennedy spoke about the future of air travel and launched the United States into the supersonic race, declaring that “this Government should immediately commence a new program …. to develop … a commercially successful supersonic transport, superior to that being built in any other country”. Behind closed doors, the United States was worried. The previous day, the nation’s largest international carrier Pan Am, had placed orders for six Concordes, shocking the White House and the head of the Federal Aviation Administration, Najee Halaby. In a memo sent the previous year in response to the signing of Concorde’s development treaty, Halaby had warned that if the Anglo French initiative was successful and went unchallenged, that the United States would be forced to “relinquish world civil transport leadership,” lose 50,000 jobs across the nation, and “conceivably, persuade the President of the United States to fly in a foreign aircraft!” Supersonic aircraft were the future, and with Pan Am’s selection of the Concorde, it was clear that the world’s strongest economy and greatest innovator was behind.

The United States’ mission to create an SST had begun three years earlier in late June, 1960 during the Eisenhower Administration, when the House Committee on Science and Astronautics recommended that Congress help fund the development of a supersonic jet. Congress was interested, but President Eisenhower was against the proposal because of its fiscal burden.

Eisenhower’s term ended on January 20, 1961, but, amidst the enthusiasm of Kennedy’s inauguration came a warning from the outgoing president. Addressing the nation three days before his departure, Eisenhower delivered a poignant, 20 minute televised speech focused on the military and the rise of the professional and continual armament industry he called the “military industrial complex.” Asserting that “we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence … by the military industrial complex,” Eisenhower warned that “the potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.” With the Cold War beginning, Eisenhower believed frivolous projects like the uneconomical SST would serve primarily to the benefit of the aircraft industry.

Though cognizant of Eisenhower’s concern about the SST expanding the military industrial complex and imposing an undue fiscal burden on the nation, many in Congress saw (like their British and French peers) that developing an SST was a necessity to remain competitive in commercial aviation. As President Kennedy asserted in the Air Force Academy commencement speech, an SST program to “maintain the Nation’s lead in long-range aircraft” would be “essential to a strong and forward-looking Nation” that would not only continue to lead the Soviet Union, but also the industries of other Western nations. In his 1966 thesis titled “The Supersonic Transport as an Instrument of National Power,” Air Force Colonel Donald Hackney agreed with Kennedy, arguing that an SST would be not only an exceptional jet commercially, but would additionally “strengthen our national military airlift capability and provide a highly productive vehicle for other military missions.” Concluding that “the magnitude of the development cost [requires] Government assistance,” Hackney asserted that financing the SST in exchange for a royalty could “quite conceivab(ly) … lead to the finest transport in the history of aviation at no cost to the taxpayer.” Adopting similar reasoning, Congress began its deliberation.

With knowledge that the Soviet Union was already working on a supersonic transport, tension was high when the “Supersonic Transport Symposium” was called in June, 1960. With two of the four papers presented focused on issues of competition and the “national prestige” of the United States, political ends of the SST project were emphasized from the start of development.

Asserting that, “unless as a nation we want to risk lagging behind the USSR in the introduction of a supersonic transport … we must start an aggressive development program without further delay,” the first paper, presented by Pearson and Pfeiffer of North American Aviation set the tone of the symposium. Presenting the opportunity an SST offered the United States, the other paper, from Burt Monesmith and Robert Bailey at rival aeronautics firm Lockheed echoed the first, declaring that “in the supersonic transport, the US has an opportunity to demonstrate to the world its technological leadership over the Soviet Union” and that “the Government would be justified in supporting the development of a supersonic transport simply for national prestige.” The Soviets had driven America into the supersonic race. The goal: a Mach 3 capable jet by 1963.

In these initial days of SST development, the United States was eager to find a national partner such as the United Kingdom or West Germany to spread the burden and risk of developing an SST. As Arnold Kotz, a Policy Planning Officer in the FAA, suggested in mid-1962,

” If the obstacles can be overcome, the West will preserve its prestige vis-a-vis the Soviet bloc; uneconomic competition for a very small market among the Western allies will be reduced or precluded; the claim on US public funds will be substantially reduced; the strain on the US private aircraft industry will be lightened while they would still achieve the largest share of the market since US airlines would presumably order the largest number of aircraft… all Western participating countries would share in the advanced technology, and there would be a definite political gain in having key Western Nations work closely together on a program of this magnitude. “

As talks continued however, technical goals for the project, and ideas regarding how work should be split between the two nations began to erode this cooperative attitude.

After the signing of Concorde’s development treaty, there was no going back. Intense lobbying for an SST began in Congress immediately. Speaking about how the Anglo-French had called on Boeing as a supplier for the Concorde project, Boeing’s William Bell declared that “the foreign threat, particularly that of the French in our air transport image and our national prestige is so great that an effort much more vigorous that our present national supersonic transport program must be organized.” Cries that the United States would lose 500,000 aviation jobs and that the military would become dependent on foreign corporations began to scare Congress into action funding a bidding process for the FAA’s specifications.

At the White House, President Kennedy balked at the Anglo-French coalition. As FAA director Halaby recalled, “When de Gaulle embraced the joint [Anglo-French] Concorde project, it seems to trigger competitiveness.” asserting that, “JFK associated the Concorde most with de Gaulle” and that when they saw each other the President would “press me on how our studies were going and how the British and French were doing,” declaring more than once that “We’ll beat that bastard de Gaulle!” President Kennedy had become obsessed. On March 1, 1963, the President spent 20 minutes on the phone with Director Halaby. Only Prince Peter of Greece received more of the President’s attention that day. With Kennedy’s dedication, however, came a caveat that he highlighted in a letter to President of the Senate and Speaker of the House on June 14, 1963. Declaring that “If at any point in the development program, it appears that the aircraft will not be economically sound, or if there is not adequate financial participation by industry in this venture, we must be prepared to postpone, terminate, or substantially redirect this program,” Kennedy had set clear boundaries for the United States’ SST project—ones that would eventually end the program.

As Lockheed, Boeing, and other firms began preliminary SST design, sentiments of American superiority began to pervade the project. At Boeing, Vernon Crunge was confident and didn’t equivocate, declaring that, “the British and French will be left to do this thing on the philosophy that is stupidity of their own and will lead them nowhere, and we shall ultimately overtake them with something more versatile, more economical and better suited to solve the problem.” Even Pan Am, treacherous patron of the Concorde, let it be known that what it really wanted was a US SST.

On November 22, 1963, everything changed. Riding in a motorcade through the streets of Dallas, shots rang out from a nearby building and Kennedy slumped down into the seat of the convertible he was riding in. The SST’s champion was dead. With Johnson’s climb to the Oval Office, ecstatic obsession for an SST was replaced by passive support. Director Halaby met less with Johnson and the men were never as close as Kennedy and Halaby had been.

Announcing on April 1, 1964, that after a rigorous overview by 210 of the country’s most skilled engineers, and aviation professionals that Boeing’s sweep-wing airframe and General Electric’s turbo-jet engines had been selected as the primary contender to build the US SST, the SST project began in earnest. Issuing an executive order on the same day to form a Presidential Advisory Committee (PAC) on the SST, President Johnson sought to lay a solid foundation for the SST program to continue. Appointing Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to chair the committee, however, Johnson had unknowingly subverted the project.

Coming to the Defense Department during the Kennedy Administration after leading the Ford Motor Company, Robert McNamara brought his obsession with efficiencies to the Cold War Department of Defense. Preferring the “economy” of intercontinental ballistic missiles, McNamara had killed the B-70 supersonic bomber program, and now turned his attention to the United States’ SST. Reflecting on the program, McNamara dismissed assertions of preserving national pride and competition with the Soviet Union, noting that:

” Right at the beginning I thought the project was not justified because you couldn’t fly a large enough payload over a long enough distance at a low enough cost to make it pay. I’m not an aeronautical engineer or a technical expert or an airline specialist or an airline manufacturer, but I knew that I could make the calculations on the back of an envelope. So I approached the SST with that bias. President Johnson was in favor of it. The question, in a sense, was how to kill it [so] I conceived an approach that said: maybe you’re right, maybe there is a commercial market, maybe what we should do is to take it with government funds up to the point where the manufacturers and the airliners can determine the economic viability of the aircraft. “

Sufficiently undermining the United States’ program with a team of economists led by SST-skeptic Stephen Enke, McNamara then turned his attention across the Atlantic.

At a meeting of the PAC-SST on March 30, 1965, CIA Director John McCone presented a report detailing the technical difficulties the Anglo-French had had with drag, and their general lack of research into the effect of sonic booms and the economics of their plane. With the report’s conclusion that the Europeans were slowing down in development, McNamara encouraged that United States program to slow down as well so that the country could focus on building the best SST possible.

With Najee Halaby’s term as FAA Director ending in July, 1965, and his replacement William “Bozo” McKee dedicated to creating an SST “economically profitable to build and operate” the SST project had lost its biggest ideologue and advocate for a pragmatist. The final blow was near.

Encountering technical problems with the mechanics and weight of its hinge system, Boeing announced that it was abandoning its sweep-wing design on October 21, 1968 and submitted a new proposal for a smaller, slender delta design four months later in January 1969. When Boeing submitted its new design, the Soviet Tuploev Tu-144 supersonic jet had already flown, and Concorde’s first flight was just two months away. Boeing and the United States were limping sorely behind the competition. As interest moved from the SST to the new Boeing 747 and its incredibly low costs per passenger mile, public opinion began to rapidly shift against the SST. Securing funding for the SST had always been an easy pitch, but when a funding bill in May, 1970 passed with only 13 votes above a majority in the House, opponents across the country saw weakness and began the final assault.

Eyed by Senator William Proxmire from Wisconsin - infamous for his “Golden Fleece Awards” that he gave monthly to highlight dubious government spending—the SST’s budget came under attack. Unconvinced by SST Project Lead William Magrudedr’s assertion that “by the time the 300th airplane is sold, all of the Government’s investment will be returned the the US Treasury, and when we sell 500 airplanes, there will be a billion dollar profit for the government,” Proxmire tore into what he saw as a blatant waste of public money. Lamenting that, “We are being asked to spend $290 million this year for transportation for one half of one percent of the people—the jet setters—to fly overseas, and we are spending $204 million this year for urban mass transportation for millions of people to get to work,” Proxmire ignited the fires of public opinion, holding a congressional hearing in May, 1970 with whitenesses carefully selected to degrade the SST as thoroughly as possible.

The final barrage came in September, 1970, when a wave of economists across the ideological spectrum—including Milton Friedman, Kenneth Arrow, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Arthur Okun who had chaired the President’s Council of Economic Advisors—dismantled the commercial viability of the project. The Nixon Administration remained in support of the project, but in a time when only half of all Americans had flown in an airplane, and 85 percent of the country opposed the SST, the administration was effectively powerless. When the House narrowly voted against funding in December 1970, a bureaucratic battle ensued through congressional committees. Six months later, on May 20, 1971, the SST died an unglamorous death when the House once again voted against funding 215-204. A slow, pragmatic, assault had dispersed the SST’s champions, and ended the program. The United States had spent $1.8 billion ($10.99 billion in 2016 adjusted dollars).

Though the United States had failed to produce even a prototype aircraft, the Soviet Union had performed only marginally better. First to fly an SST, the Soviet Union initially seemed to have a large advantage over its Western competition. As time progressed, however, the world began to recognize that while the Soviet jet was first, it was clearly inferior to the Concorde. From the small canards it needed to deploy for stability while landing, to the air conditioning of the Tupolev jet, which required a separate tank of water as a heat sink where Concorde employed its fuel tank.

As time progressed, the rush to produce the Tu-144 would prove to be tragic. Seeing Concorde’s spectacular performance the previous day at the 1973 Paris Airshow, when it was the Soviet jet’s turn the pilots tried to mimic Concorde’s steep initial climb and hard banks. Diving from 4,000 feet, however, the plane broke apart and debris rained down into the Parisian suburb of Goussainvile, killing all 6 onboard the aircraft and 8 residents of the town.

After the airshow crash, the Tu-144 flew cargo and occasionally passengers from Moscow to Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan, but, after an in-flight fire brought another Tu-144 crashing down in 1978, the plane was removed from regular service.

Thus, of the three initial programs, only the Concorde lived to see regular commercial service. The Anglo-French coalition had beat the Soviets in the field of quality, and the United States in the field of determination. At 23 miles a minute—faster than a rifle bullet—it offered those fortunate enough to fly her unprecedented speed and unsurpassed luxury. Contrasted with the general deglamorization of air travel and the continued demise of the empire, Concorde upheld the sophistication of both air travel and British industry and technology. Flown with the Red Arrows—the Royal Air Force’s Aerobatic Team—to commemorate the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, Queen Elizabeth’s Golden (50th) Jubilee in 2002, and other notable events, the Concorde became an emblem of post-empire Britain, and a symbol of pride. In a video produced by British Airways to mark Concorde’s 2003 retirement, pilot, after stewardess, after business executive, recalled their fondness for their countries “national symbol for celebration” and remarked on how she stood out as special because of “the quality of the work, the minds, the skill, the talent, the commitment that went into it.”

Stretching beyond the elite group of people who regularly flew her, Concorde’s appeal transcended class barriers. Even at the end of her 27 year career, Concorde’s “unique blend of power, grace, [and] beauty” continued to draw people to “look up whenever and wherever she [took] to the skies.” Commenting on Concorde’s mass appeal, Mike Bannister, Chief Concorde Pilot for British Airways, asserted in a 2002 explained that “[Concorde] turns the heads of people who have no need to fly on it,” not because they are jealous of those who can afford to fly on the plane, but because they are a “part of a country that is capable of putting such a beautiful aircraft into the air.” For the thousands of British and French citizens who worked on Concorde’s development and construction, Concorde’s “fusion of art and technology” conjures “up a sense of pride and fond affection.”

The first and only commercial supersonic aircraft, Concorde offered passengers travel at twice the speed of sound—cutting travel time on its flagship New York to London or Paris routes from seven hours, to just over three. The evening flight outsped earth’s rotation. Passengers could watch the sun set, sipping cocktails in Heathrow’s exclusive Concorde Lounge, board the plane at night, and cross the Atlantic, to once again watch the setting sun from one of Manhattan’s rooftop restaurants.

Concorde’s supersonic career came to an end in 2003, when rising fuel costs and a constant uptick in the cost of maintaining the fleet made Concorde economically unbearable. Before this point though, the 16 plane fleet had found a niche carrying the rich and famous across the Atlantic at twice the speed of sound. The plane never made much money—the oil shocks of the 1970s and 90s made sure of that—and the British and French government didn’t make much money either, selling the first 9 planes to their national carriers for £80 million apiece and the remaining 7 for just £1 apiece, but the Concorde inspired two nations for half a century. As a middle-aged woman from the southern English city of Exeter, who knew many of those who built the plane remarked “It’s our aeroplane really.”

Standing invitation (inspired by Patio11 who also has some good tips on how to approach this): if you want to talk about hard tech or systems, I want to talk to you.

My email is my full name at gmail.com.

- I read every email and will almost always reply.

- I like reading things you’ve written.

- I go to conferences to meet people like you.

- Meetings outside of conferences are tougher to fit with my schedule - let’s chat over email first. Specificity and being concise makes it easy for me to reply :)