Japan - So Many Nuggets

10 Jan 2020

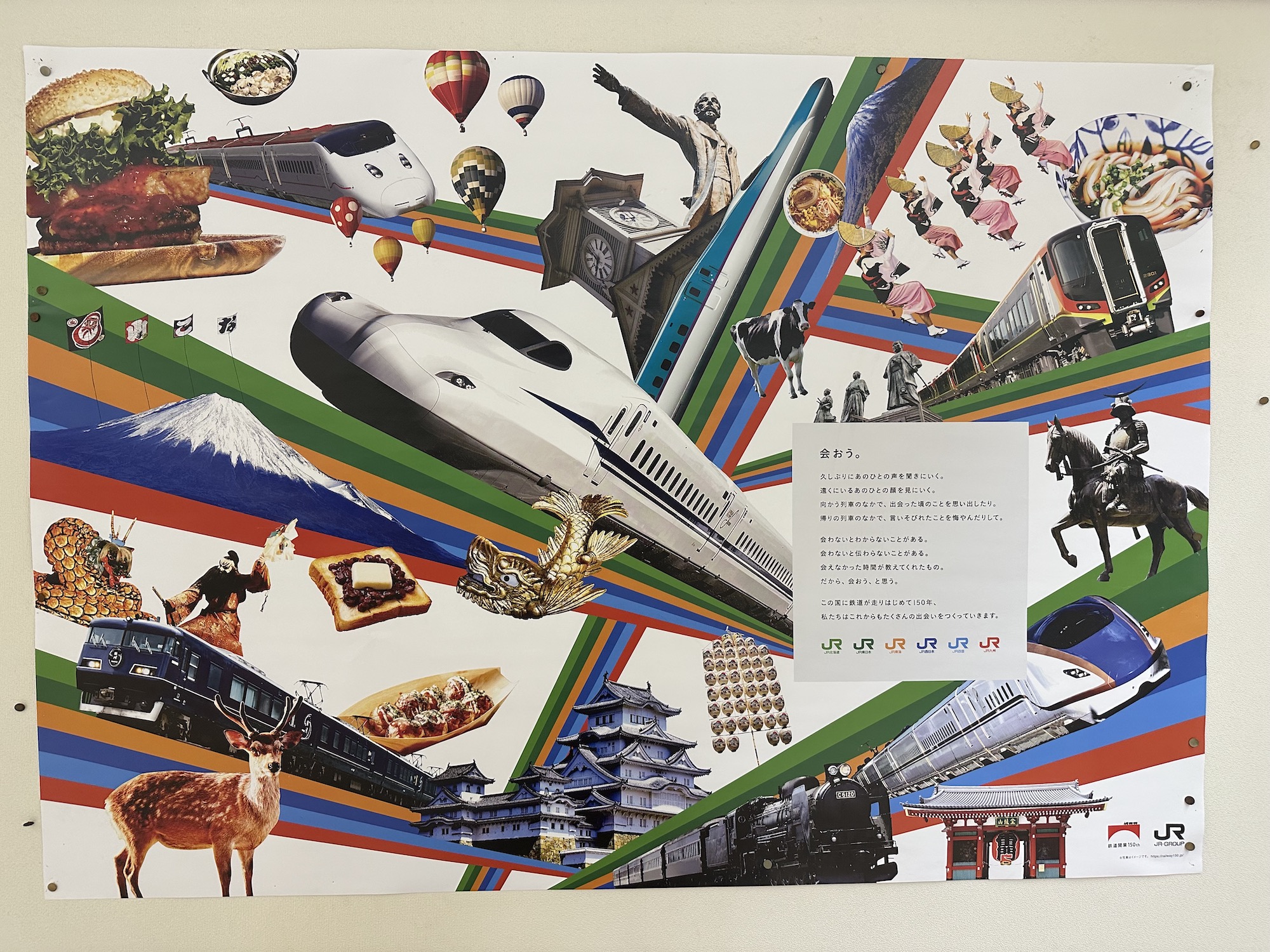

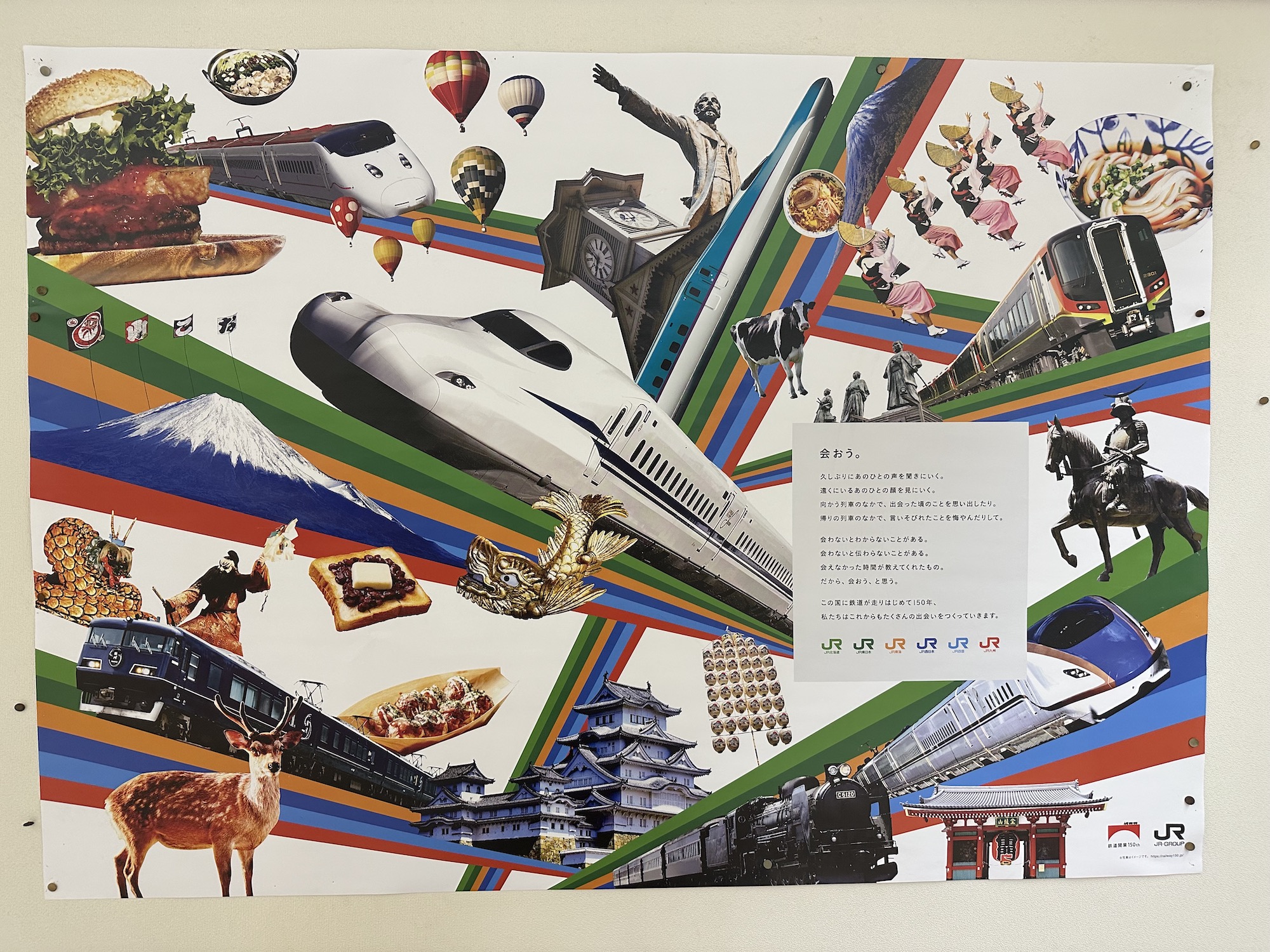

I spent a bit of the holiday season in Japan visiting friends and riding the Shinkansen (bullet train). There is a lot to like. From clean, sprawling, dense, and affordable cites, to strangers offering to help an oftentimes extremely lost Gaijin (foreigner).

Yet, I leave the Land of the Rising Sun with more conflicted thoughts than I have for my own home. Things are so familiar and so different. There is so much peace and so much chaos. There is so much hope and so much despair.

I am also accumulating quotes about things far faster than I am writing about them so I thought I’d grab ones about Japan and smoosh them all together in the hope I can simulate the same conflict I feel as I depart.

The Economist recently published a special on housing in the west. One of the articles details how housing policies have increasingly caused wealth to be transferred from the poor, young, and members of ethnic minorities to those who are richer, older, and in the ethnic majority but calls out Japan for largely escaping this trap.

Overall housing costs in America absorb 11% of GDP, up from 8% in the 1970s. If just three big cities—New York, San Francisco and San Jose—relaxed planning rules, America’s gdp could be 4% higher. That is an enormous prize.

It does not have to be this way. Not everywhere is afflicted with every part of the housing curse. Tokyo has no property shortage; between 2013 and 2017 it put up 728,000 dwellings—more than England did—without destroying quality of life. The number of rough sleepers has dropped by 80% in the past 20 years.

In Japan, zoning limitations (height, “setbacks” from other properties, density, etc) are much less restrictive than in the United States and other Western nations. Building projects (often at a massive scale) continue with limited challenge1, and though Japanese culture is generally more communitarian which probably explains some of the permissiveness, Japan also lacks the explosive growth in property values see in centers of the West’s housing crisis such as the San Francisco Bay Area.

First, let us consider the wealthy Japanese families of the late-twentieth century. During the 1980s, Japan’s economy experienced an incredible boom. From 1985 to 1989, the Nikkei stock index tripled in value, reaching an all-time high of 38,957.11 yen.

By 1993, half of the world’s billionaires were Japanese, and they held almost 13.6% of the global wealth of billionaires. Today, that figure has shrunk to only 1.4%. On the other hand, while there were no billionaires in mainland China in 1993, today’s top-earners in China hold 8.1% of the world’s private wealth.

What caused this extreme reversal in fortune for wealthy Japanese families? Put simply, these Japanese billionaires mismanaged their fortunes. As Japanese real estate appreciated, Japan’s wealth grew. This extreme and rapid appreciation of real estate and stock market valuations, however, created an enormous asset bubble. During the 1990s, the Nikkei index saw sharp declines, and real estate in Japan quickly lost value. By 2004, Tokyo residences were worth only 10% of their 1980s peak value. Similarly, the value of Japan’s most prized land in Tokyo’s Ginza business district lost 99% of its value. Moreover, twenty years after the 1989 peak, the Nikkei index closed at 7,054.98 on March 10, 2009, a full 82% lower.

Due to the combination of falling real estate values and the depreciation of Japanese equities, many Japanese billionaires saw their fortunes disappear. Billionaires could have seen their fortunes grow through intelligent, diversified, and calculated investments that compounded over years. Instead, their wealth is lower today than it was in 1989. While billionaires in the rest of the world grew wealthier, Japanese billionaires only experienced wealth stagnation and loss.

The Nikkei closed 2019 at 23,566.72, ~40% below 1989’s all-time high. It has been 31 years since 1989.

Japanese equities often swing wildly from year to year. This is surprising given that Japan is the world’s third largest economy (and second largest stock market), the index is dominated by large multinationals who don’t seem to be facing much local disruption, and the country has a strong institutions, rule of law, and general stability.

Last 30 Years Change in the Nikkei:

| Year |

Closing Level |

Percent Change in Index |

| 1989 |

38,915.87 |

29.04 |

| 1990 |

23,848.71 |

-38.72 |

| 1991 |

22,983.77 |

-3.63 |

| 1992 |

16,924.95 |

-26.36 |

| 1993 |

17,417.24 |

2.91 |

| 1994 |

19,723.06 |

13.24 |

| 1995 |

19,868.15 |

0.74 |

| 1996 |

19,361.35 |

-2.55 |

| 1997 |

15,258.74 |

-21.19 |

| 1998 |

13.842,17 |

-9.28 |

| 1999 |

18,934.34 |

36.79 |

| 2000 |

13,785.69 |

-27.19 |

| 2001 |

10,542.62 |

-23.52 |

| 2002 |

8,578.95 |

-18.63 |

| 2003 |

10,676.64 |

24.45 |

| 2004 |

11,488.76 |

7.61 |

| 2005 |

16,111.43 |

40.24 |

| 2006 |

17,225.83 |

6.92 |

| 2007 |

15,307.78 |

-11.13 |

| 2008 |

8,859.56 |

-42.12 |

| 2009 |

10,546.44 |

19.04 |

| 2010 |

10,228.92 |

-3.01 |

| 2011 |

8,455.35 |

-17.24 |

| 2012 |

10,395.18 |

22.94 |

| 2013 |

16,291.31 |

56.72 |

| 2014 |

17,450.77 |

7.12 |

| 2015 |

19,033.71 |

9.07 |

| 2016 |

19,114.40 |

0.42 |

| 2017 |

22,764.94 |

19.10 |

| 2018 |

20,014.77 |

-12.08 |

| 2019 |

23,656.62 |

18.20 |

The government has tried many things to encourage the economy to grow, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s “Abenomics” efforts with quantitative easing, fiscal stimulus, and structural reforms to make the country more competitive abroad have been a key push that started in 2012.

As a Wikipedia Article about Japan’s world-high national debt to GDP ratio explains:

Abenomics led to rapid appreciation in the Japanese stock market in early 2013 without significantly impacting Japanese government bond yields, although 10-year forward rates rose slightly. Around 70% of Japanese government bonds are purchased by the Bank of Japan, and much of the remainder are purchased by Japanese banks and trust funds, which largely insulates the prices and yields of such bonds from the effects of the global bond market and reduces their sensitivity to credit rating changes. Betting against Japanese government bonds has become known as the "widowmaker trade" due to their price resilience despite fundamentals to the contrary.

Capital staying within a large developed economy makes plenty of sense but Japan still exports a far greater share of its goods than the United States2 and has remained consistently competitive in the automotive, electronics, electrical machinery, and medical device spaces.

Japan builds particularly good cars, and the gap between Japan and the rest of the world was even wider in the 80s. Things were so bad at GM’s Fremont plant they shut it down until they started working with Toyota on their “New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc” (NUMMI) joint venture.3

One of the expressions was, you can buy anything you want in the GM plant in Fremont,” adds Jeffrey Liker, a professor who studied the plant. “If you want sex, if you want drugs, if you want alcohol, it’s there. During breaks, during lunch time, if you want to gamble illegally—any illegal activity was available for the asking within that plant.” Absenteeism was so bad that some mornings they didn’t have enough employees to start the assembly line; they had to go across the street and drag people out of the bar.

When management tried to punish workers, workers tried to punish them right back: scratching cars, loosening parts in hard-to-reach places, filing union grievances, sometimes even building cars unsafely. It was war.

In 1982, GM finally closed the plant. But the very next year, when Toyota was planning to start its first plant in the US, it decided to partner with GM to reopen it, hiring back the same old disastrous workers into the very same jobs. And so began the most fascinating experiment in management history.

Toyota flew this rowdy crew to Japan, to see an entirely different way of working: The Toyota Way. At Toyota, labor and management considered themselves on the same team; when workers got stuck, managers didn’t yell at them, but asked how they could help and solicited suggestions. It was a revelation. “You had union workers—grizzled old folks that had worked on the plant floor for 30 years, and they were hugging their Japanese counterparts, just absolutely in tears,” recalls their Toyota trainer. “And it might sound flowery to say 25 years later, but they had had such a powerful emotional experience of learning a new way of working, a way that people could actually work together collaboratively—as a team.”

Three months after they got back to the US and reopened the plant, everything had changed. Grievances and absenteeism fell away and workers started saying they actually enjoyed coming to work. The Fremont factory, once one of the worst in the US, had skyrocketed to become the best. The cars they made got near-perfect quality ratings. And the cost to make them had plummeted. It wasn’t the workers who were the problem; it was the system.

An organization is not just a pile of people, it’s also a set of structures. It’s almost like a machine made of men and women. Think of an assembly line. If you just took a bunch of people and threw them in a warehouse with a bunch of car parts and a manual, it’d probably be a disaster. Instead, a careful structure has been built: car parts roll down on a conveyor belt, each worker does one step of the process, everything is carefully designed and routinized. Order out of chaos.

With relations between labor and management portrayed so positively, I wasn’t super surprised to hear that in the 50 years of the Shinkansen bullet train’s operation, none of the network’s 10+ billion passengers have died in a train accident. All of this in a system whose average delay was 0.9 minutes which include delays caused by the earthquakes and typhoons which often strike Japan. While the dueling mandate of safety and punctuality hasn’t resulted in a tragedy on the Shinkansen, a speed related derailment of a commuter line outside of Osaka in 2005 brought scrutiny to the punctuality standards enforced upon train drivers.

Drivers face financial penalties for lateness as well as being forced into harsh and humiliating retraining programs known as nikkin kyōiku (日勤教育, "dayshift education"), which include weeding and grass-cutting duties during the day. The final report officially concluded that the retraining system was one probable cause of the crash. This program consisted of severe verbal abuse, forcing the employees to repent by writing extensive reports. Also, during these times, drivers were forced to perform minor tasks, particularly involving cleaning, instead of their normal jobs. Many experts saw the process of nikkin kyoiku as a punishment and psychological torture, and not as driver retraining.

A similar severity is brought in the criminal justice system. After the 1995 sarin-gassing of the Tokyo Subway by a doomsday cult, the response was more severe than the United States’ response to the Boston Marathon Bombing 18 years later.

When the police finally moved, they did so with overwhelming force. Two days after the subway attack, 2,500 of them raided a dozen cult properties with riot gear, gas masks and caged canaries. (With a straight face, a spokesman said they were investigating a kidnapping.) They arrested Aum acolytes for jaywalking and bicycle theft, and questioned them for weeks to find out where Mr Asahara was hiding. (Suspects can be held for 23 days without charge in Japan.) They eventually found him in a crawl-space in a building they had already raided several times.

It then took 23 years to hang him. The outcome of his trial was never in doubt: the conviction rate in Japanese courts is over 99% and there were literally warehouses full of evidence against him. Yet his first trial lasted seven years—like many in Japan, it was not held on consecutive days. His appeals dragged on until 2006. He lingered another 12 years on death row, never knowing each morning whether he would be hanged that day. This is how Japan treats the condemned. It is not how anyone should be treated, not even a monster like Mr Asahara.

At the same time, institutions like the police are almost always remarkably personable in everyday interactions.

Wherever I travel somewhere, I ask myself if I would live there, and if I would raise children there.4 Here too I struggle to make a decision. One of my favorite bloggers — Patrick McKenzie — lives in Japan and offers this anecdote:

People often ask me why I live in Japan.

A part: is that it is a place where I could take my daughter to lost-and-found to ask about an acorn, knowing that someone would return an acorn, knowing that someone would clearly expect a lost acorn to be returned and therefore ask.

There are so many things I like about Japan. The streets are clean and safe, public transit is often faster than a car, employees take pride in their work and are extremely helpful. At the same time, I struggle to think about what it would mean to live in an economy that doesn’t really grow, and with a social structure much more rigid than the one I am used to.

Since I am still young and trying to grow and learn as much as possible, I worry how these things might change and limit me. But, as a place to live with a family unit — especially with young children - I think Japan offers most of the world stiff competition.

Let’s stay in touch - I’d love to hear your thoughts on this and other posts! Email me at spence dot burleigh at gmail and sign up to get the next post in your inbox.

1: Though the construction of Tokyo’s Narita Airport was extremely hard fought — protestors built a 200 foot tower at the end of a runway)

2: 16.1% vs 11.9% — though both are far below the world average of 28.5%

3: (This American Life)[https://www.thisamericanlife.org/403/nummi-2010] did a story about the plant when it was closed in 2010. It later sold to Tesla — becoming that company’s first factory.

4: I ignore a good deal of practical things (language, proximity to family, mostly what I would do for work) and be somewhat flexible with my (Western) values when I think about this. I try to make asking myself if I would live somewhere a more micro than macro question about the livability of a place and the way I feel about it. Asking yourself if you’d raise kids somewhere is much more of a macro and culture question since environment will define a big part of who a kid becomes (though I’d also assume they would be in an international school…)

Related reading:

This is honestly just more quotes about Japan with some interjected thoughts that has less flow than above :/

Everyone loves cross laminated timber!

Japan’s government has long advertised the advantages of wooden buildings, and in 2010 passed a law requiring it be used for all public buildings of three stories or fewer.

It has been interesting to contrast Japan with much more familiar Germany. Japanese War Crimes during the Second World War were exhaustive and the country has responded very differently from Germany and continues to be a sore point with its neighbors.

Denial and revisionist accounts of the Nanjing Massacre where 50,000 to 300,000 people were murdered by Japanese troops at the start of the Second World War is a “staple of Japanese Nationalism.” The Chinese took to calling their invaders “Japanese Devils” during the war and the phrase seems to still see occational use.

《谶言一种》

"A Kind of Prophecy"

村里的老人都说

Village elders say

我跟我爷爷年轻时很像

I resemble my grandfather in his youth

刚开始我不以为然

I didn’t recognize it

后来经他们一再提起

But listening to them time and again

我就深信不疑了

Won me over

我跟我爷爷

My grandfather and I share

不仅外貌越看越像

Facial expressions

就连脾性和爱好

Temperaments, hobbies

也像同一个娘胎里出来的

Almost as if we came from the same womb

比如我爷爷外号竹竿

They nicknamed him “bamboo pole”

我外号衣架

And me, “clothes hanger”

我爷爷经常忍气吞声

He often swallowed his feelings

我经常唯唯诺诺

I'm often obsequious

我爷爷喜欢猜谜

He liked guessing riddles

我喜欢预言

I like premonitions

1943年秋,鬼子进

In the autumn of 1943, the Japanese devils invaded

我爷爷被活活烧死

and burned my grandfather alive

享年23岁

at the age of 23.

我今年23岁

This year i turn 23.

-- 18 June 2013

Similar issues with Korea where Japan ruled from effectively 1895 when assassins snuck into the palace, killed the empress and burned her body.

In 2017, Japan recalled its ambassador from South Korea in protest of a statue to honor the “comfort women” sex slaves taken by the Japanese army across from the embassy. Tensions have even run high in the United States when San Francisco approved a statue of a comfort woman and the mayor of Osaka (Japan’s second largest city) threatened to dissolve the “sister city” relationship the two cities had shared for over 50 years. Unfortunately it does’t seem like this will be figured out anytime soon.

History gives the Japanese and the Koreans ample grounds for mutual distrust and contempt, so any conclusion confirming their close relationship is likely to be unpopular among both peoples. Like Arabs and Jews, Koreans and Japanese are joined by blood yet locked in traditional enmity. But enmity is mutually destructive, in East Asia as in the Middle East. As reluctant as Japanese and Koreans are to admit it, they are like twin brothers who shared their formative years. The political future of East Asia depends in large part on their success in rediscovering those ancient bonds between them.

Standing invitation (inspired by Patio11 who also has some good tips on how to approach this): if you want to talk about hard tech or systems, I want to talk to you.

My email is my full name at gmail.com.

- I read every email and will almost always reply.

- I like reading things you’ve written.

- I go to conferences to meet people like you.

- Meetings outside of conferences are tougher to fit with my schedule - let’s chat over email first. Specificity and being concise makes it easy for me to reply :)